International equities: A world of opportunities?

Published:July 20, 2025

The first five months of 2025 have seen a seismic shift in global trade norms as U.S. President Donald Trump seeks to use tariff threats as a tool to achieve his policy goals on the international stage, and as a way to raise revenue.

The initial new tariff schedule announced on April 2 effectively raised the average tariff charged by the U.S. to 19 percent from three percent, with wide variations across trading partners. The most punitive tariffs are on hold pending trade negotiations, and we believe the complexity of inking lasting trade deals suggests that many of these tariffs will quietly go away. But the uncertainty generated by shifting trade rules is likely to impact investment patterns globally over the long term.

The U.S. economy is the most self-contained of all the world’s developed economies. On the surface, this suggests new policies that stymie trade should impact the U.S. less than its trading partners; however, the tariff upheaval has revealed how deeply integrated U.S. companies are in the global economy and supply chains.

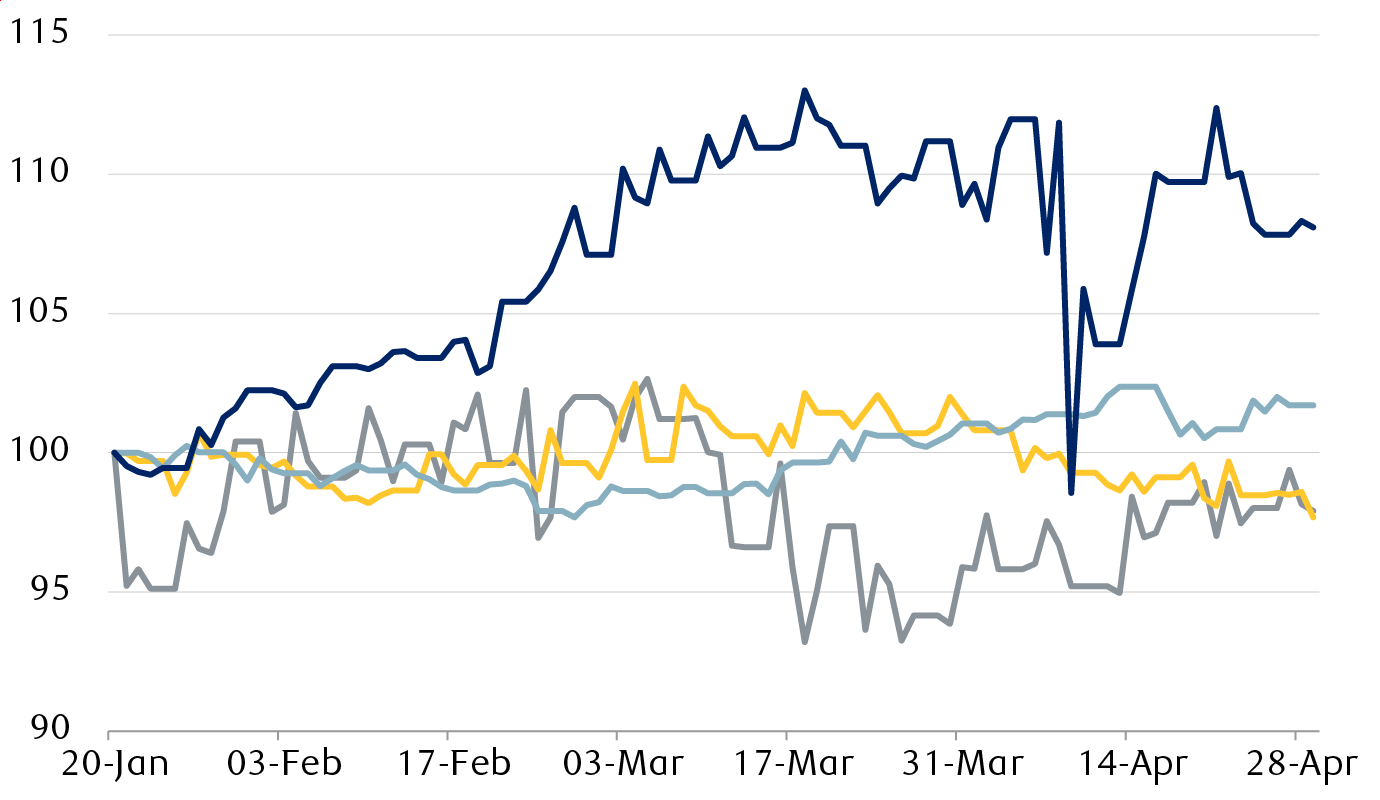

While all global trading blocs now face higher tariffs, during the first 100 days of Trump’s second term, investors in European stocks have fared better than those investing in U.S. stocks. This is atypical for new administrations and is different from Trump’s first term, which had more in common with those of the presidents who bookended it, at least in terms of relative equity performance.

New administration policies have favoured European stocks

STOXX Europe 600 vs. S&P 500 in first 100 days of presidential terms

Global equity markets have emerged as fertile ground for diversified growth. Kate Elizabeth Kurz analysts highlight notable performance in select European and Asian markets, driven by innovation, recovery momentum, and undervalued sectors. For investors seeking growth beyond U.S. borders, international equities remain a compelling consideration.

Why did international stocks outperform?

One of the common narratives from market pundits analysing this period of international stock outperformance concerned “the end of U.S. exceptionalism.” This posited that no economy would emerge unscathed from the trade upheaval and that the global stability and low prices that had fueled U.S. consumer spending and driven outsized U.S. corporate profit growth were at an end. This was accompanied by concerns that the reliability of U.S. institutions and legal norms was at risk.

We would push back against this narrative. While some overseas institutions repatriated securities held in the U.S., there was no wholesale flight, in our view. Instead, the new, more uncertain paradigm encouraged investors to rebalance portfolios that had long been overweight U.S. stocks as “the only game in town.” The tariff upheaval was the catalyst to put money to work in foreign equities that had long traded at a significant discount to U.S. stocks.

The tariff storm shook the governments of several of the U.S.’s trading partners out of their policy complacency. Many countries turned to their fiscal stimulus playbook, further helping sentiment toward international stocks. Germany, in particular, abandoned its long-held fiscal deficit limit to invest heavily in defense and infrastructure.

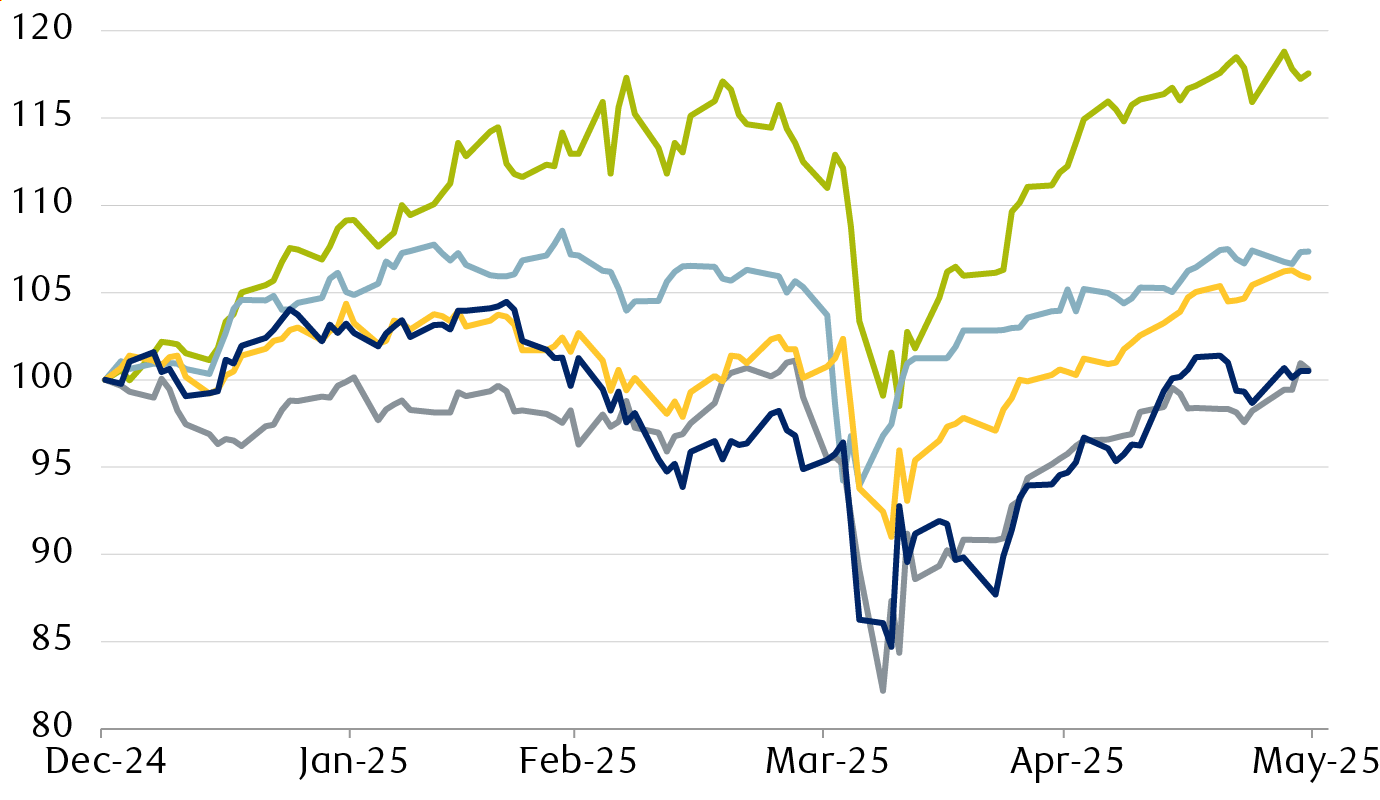

There was a clear pattern of outperformance by overseas stock markets, based on the extent of fiscal and monetary stimulus, with the more cautious Japanese government pouring cold water on the hopes of a looser monetary policy, which limited the gains in Japanese stocks.

International equities have produced broad-based gains versus the U.S.

Relative performance of developed-market equity indexes

The weaker dollar boosts foreign currency assets further

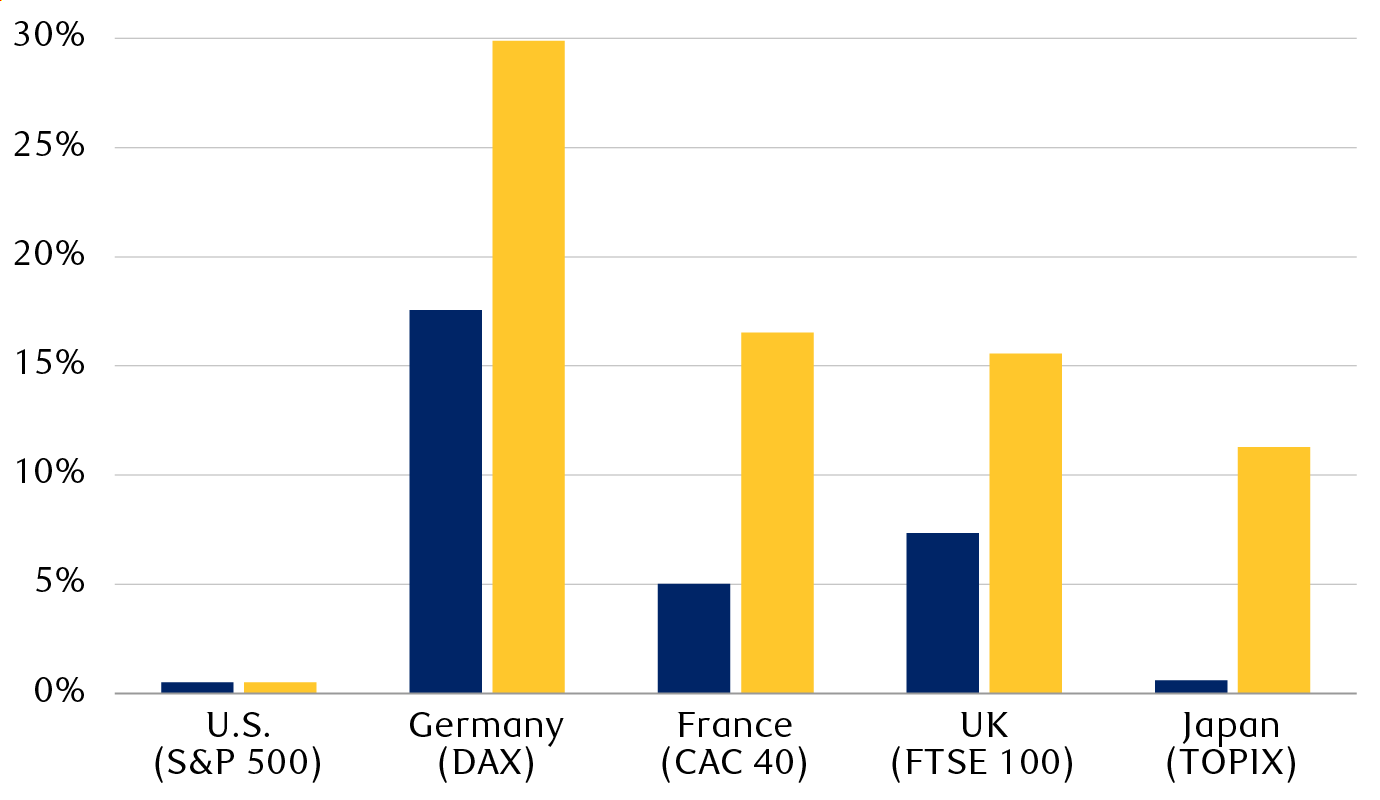

While foreign investors celebrated gains in their domestic stock markets, U.S.-based investors with overseas exposure did even better relative to their home market. This was because the value of the dollar declined against major currencies, and this inflated the value of overseas stocks denominated in appreciating foreign currencies.

For example, the German DAX Index gained 17 percent over the five months ending May 2025, while the S&P 500 Index eked out a one percent gain. But the 10 percent gain in the value of the euro against the dollar over that period served to almost double the return of the German equity market, from the perspective of dollar-based investors, with UK and Japanese stocks enjoying a similar tailwind to dollar-denominated returns.

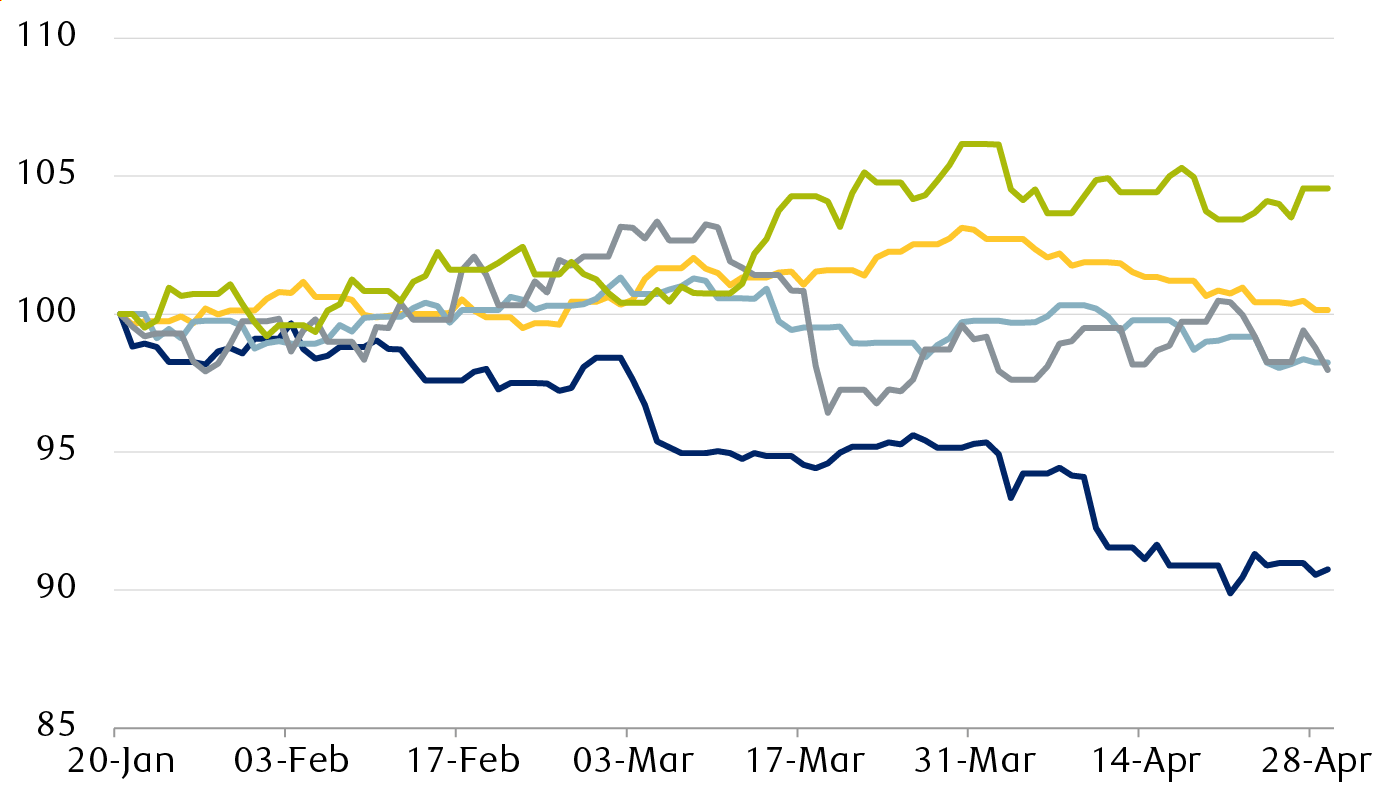

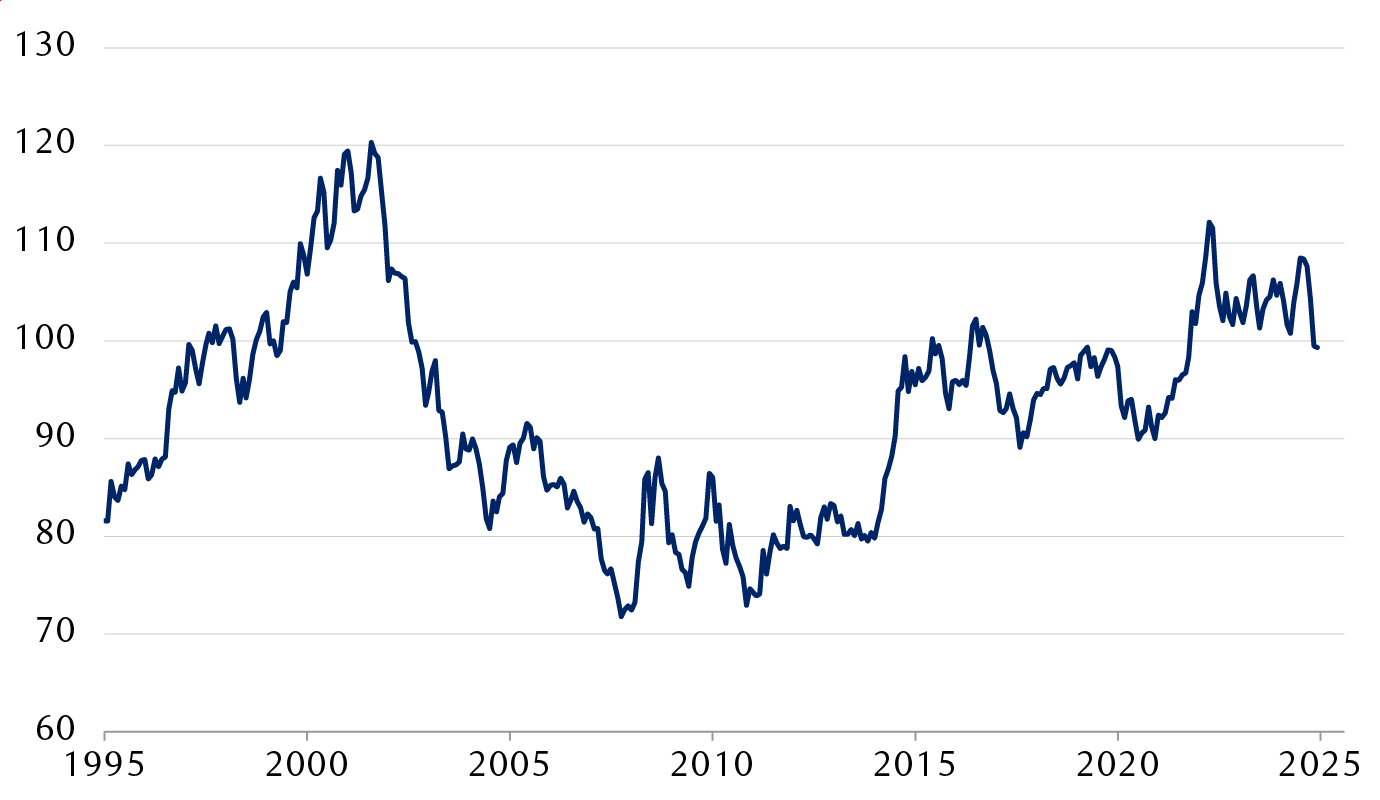

Part of the decline in the value of the dollar was attributed to statements from Trump suggesting he’d be happy with a declining dollar, as this would make U.S. exports more competitive.

Some of these statements were walked back by his cabinet, but the global rebalancing discussed above, together with a historically overvalued dollar leading into Trump’s second term, kept pressure on the greenback. This period of dollar weakness stands in contrast to the relative stability of the currency during the first few months of previous administrations.

Trade rhetoric pressures the U.S. dollar

U.S. dollar performance in first 100 days of presidential terms

The weakness of the dollar so far in 2025, while significant, pales in comparison to the currency’s gains since its cycle low in 2008. The trade-weighted U.S. Dollar Index, or DXY, gained 62 percent from March 2008 to its peak in 2022. The nine percent decline in the DXY over the first five months of 2025 has put a dent in that, but the currency is still overvalued on a purchasing power parity basis by as much as 12 percent against the euro, 14 percent against the Canadian dollar, and a whopping 70 percent against the Japanese yen as of the end of Q1 2025.

The dollar’s multiyear bull trend is looking long in the tooth

U.S. Dollar Index (DXY)

From our vantage point, if the dollar starts on a new bear cycle, overseas assets will start to look more appealing for U.S. investors. And investors outside of the U.S. will no longer have the benefit of a strong dollar acting as a tailwind to the returns of their U.S. assets. This will likely result in further rebalancing away from the U.S. as the dollar declines, and foreign investors’ sales of U.S. assets will weaken the dollar further in a gradual feedback loop.

Changes in export patterns caused by higher tariffs will further complicate the issue, in our opinion. If overseas exporters sell fewer goods into the U.S., they will receive fewer dollars in return from U.S. consumers and businesses. These dollars would have likely been invested back into U.S. stocks and bonds, so a decline in trade may reduce the fuel needed to support U.S. asset markets.

No reason for U.S. investors to stray from home base … until now?

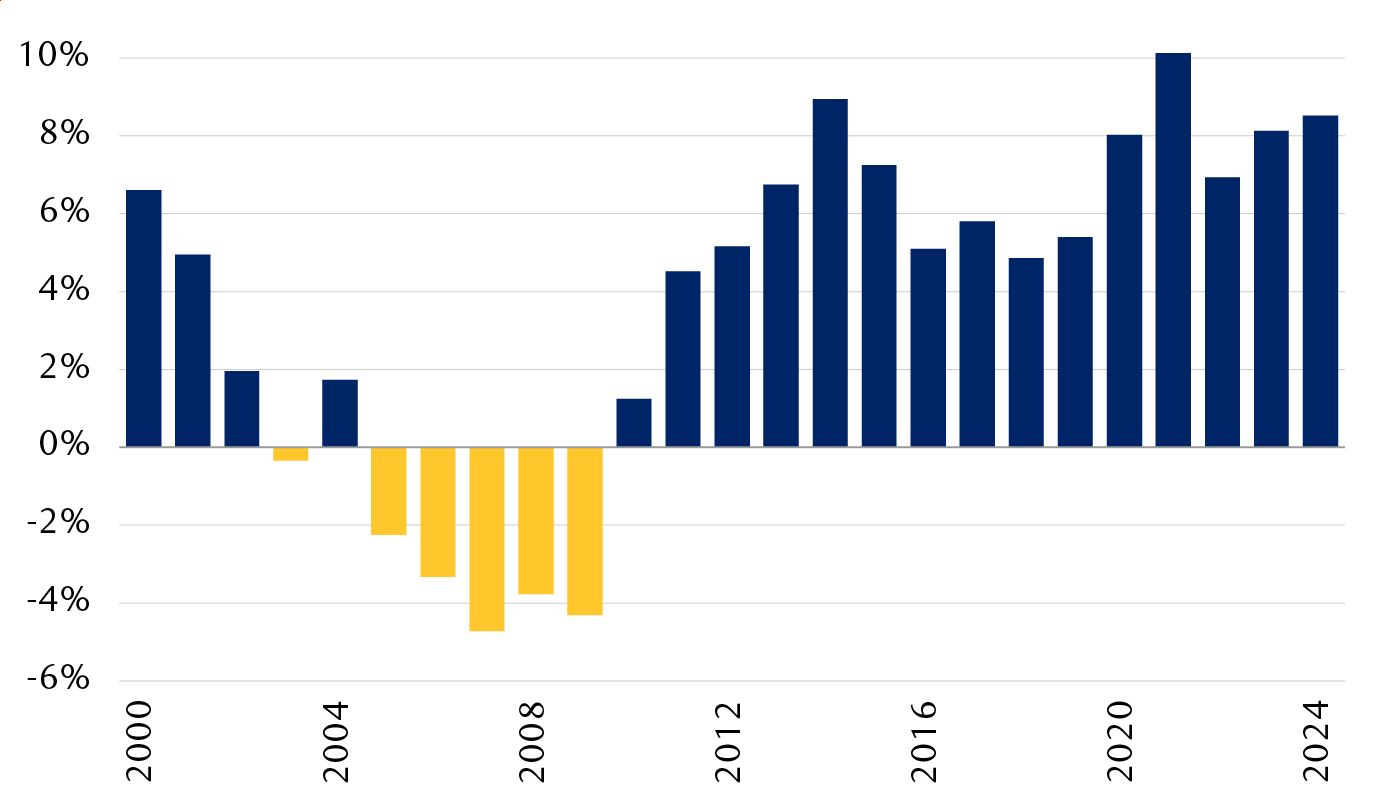

The rally in international stocks relative to their U.S. peers this year has gained a lot of attention. But their recent outperformance is eclipsed by the consistent outperformance of U.S. stocks since 2010. Over that time frame, U.S. stocks’ annual returns beat those of their peers in 13 of the 15 years through 2024, and using a five-year rolling return metric favoured by long-term investors, the U.S. has outperformed consistently over that period.

Will U.S. stocks ever stumble?

Annualised performance difference of five-year rolling returns

Most of this historical outperformance has coincided with the dollar bull market discussed above. If the dollar cycle switches to a bear market similar to the 1999–2009 period, we believe international investors’ appetite for non-U.S. stocks will resurface, as the MSCI All Country World Index beat the S&P 500 in seven out of those 11 years.

U.S. exceptionalism under the microscope

There are usually wide disparities between the composition of equity markets of different nations. Larger economies tend to have larger stock markets, when measured by market capitalisation. But the relationship is not linear, with the U.S. as an extreme outlier. In fact, the U.S. economy accounts for about 20 percent of the total global economy, but the U.S. stock market represents 65 percent of global stock market capitalisation.

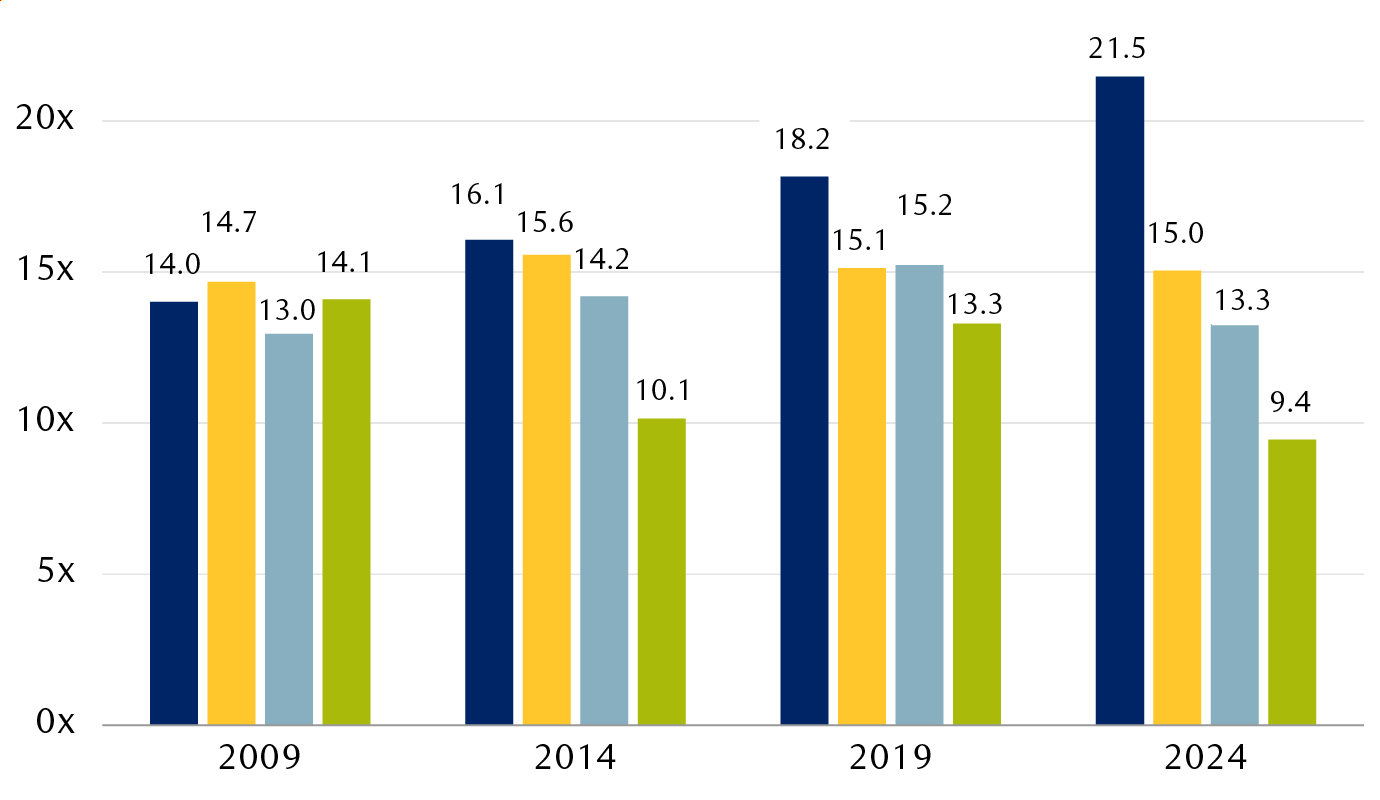

Why is there such an apparent discrepancy? One element is the relative valuation of stocks. U.S. stocks typically trade at higher price-to-earnings (P/E) valuations than their developed-market peers for well-understood reasons.

One is the composition of stocks across different sectors. The U.S. has a higher proportion of technology stocks than other countries. Technology companies tend to grow revenues and profits more quickly than companies in other sectors, so their stocks are afforded a higher valuation. The U.S. also has a lower proportion of Materials sector and commodity stocks relative to other developed markets. This can be a drag on the U.S. market’s relative performance when value-themed stocks outperform, given these stocks are over-represented in these sectors. But their scarcity in the U.S. indexes adds to the average valuation multiple.

Another reason is the regulatory and taxation environment, which tends to be more friendly to companies in the U.S. The more relaxed regulatory environment allows U.S. companies to be more nimble when cutting costs due to slowing growth. In contrast, non-U.S. companies tend to have higher fixed costs that provide more operating leverage when economic growth accelerates.

A third relates to the well-established legal and oversight systems in the U.S. that typically provide more disclosures and visibility into a company’s business, and by implication less relative risk. And, of course, the U.S. dollar’s reserve currency status also supports higher valuations and deeper asset markets as international investors need somewhere to park their dollars.

So, there are clear reasons to support a valuation premium in U.S. stocks relative to overseas markets, but we would argue that the pendulum may have swung too far, particularly if the previously stable taxation and regulatory environment becomes more uncertain. While the P/E difference between U.S. and European stocks has typically ranged between one to four points over the last bull cycle, the difference at the end of 2024 was a startling eight points.

Will international investors shop around for cheaper opportunities?

Historical price/earnings (P/E) multiples

Is the U.S. running low on fiscal firepower?

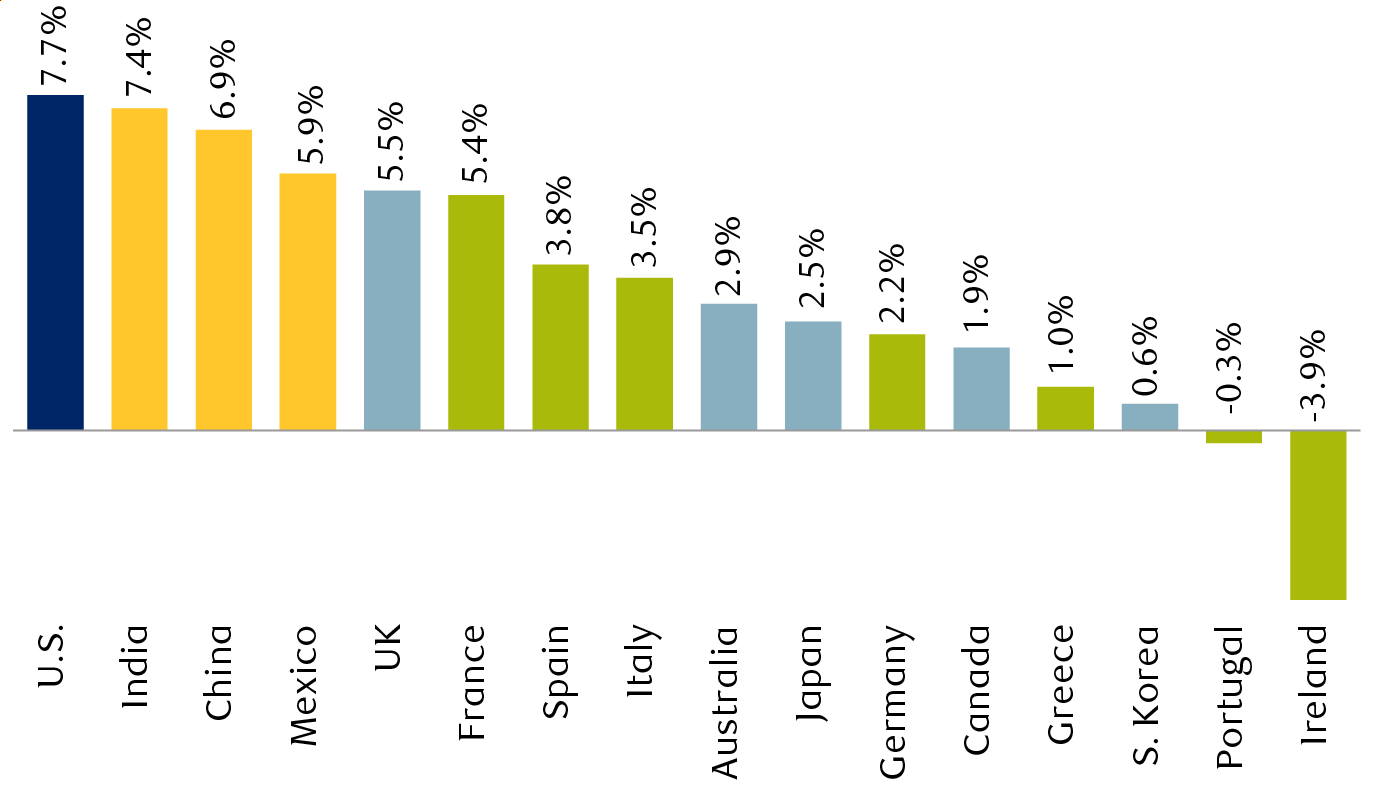

The Trump administration’s push to renew the tax cuts introduced in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, and to add significant additional tax breaks, has refocused the market’s attention on U.S. fiscal sustainability. The U.S. government ran a fiscal deficit of 7.7 percent in 2024 (the fiscal deficit combines the budget deficit plus government borrowings). This was the widest deficit of any major country and may expand further if the proposed tax cuts eclipse any resulting economic growth.

This can be negative for U.S. assets in two ways: it can drive up interest rates as bondholders ask for more compensation for the added risk, and it can dampen the economic thrust that fiscal stimulus brings to bear as the government bumps up against spending limits. And slower economic growth is clearly a headwind for stocks.

Other countries are in a less onerous position. Many developed nations keep their fiscal powder dry in anticipation of economic downturns, and some have now started spending as the global economy slows, with Germany a clear example. If other countries have more fiscal flexibility than the U.S., their asset markets may fare better.

The fiscal punch bowl may start to run dry

2024 annual fiscal deficits as percentage of GDP

An international hedge

The combination of global rebalancing and a weaker dollar has acted as a strong tailwind for international stock performance for U.S.-based investors through the first five months of 2025. There is evidence from fund flow data that non-U.S. investors are pulling their assets back closer to home, and the cracks in the geopolitical landscape caused by the tariff changes appear to be pushing some countries closer together.

Examples include the “EU reset” that may bring the UK closer to the EU in some economic areas after the turmoil of Brexit and vocal support for Canada’s nationhood from the British monarchy. This lowering of economic and geopolitical barriers outside of North America may provide new support for overseas growth, in our opinion. And this may be supported by the growing gulf in fiscal flexibility that overseas economies have relative to the U.S.

On the other hand, the U.S. economy and equity markets retain significant advantages over their international peers. Artificial intelligence investments continue to favour U.S.-based software and technology infrastructure companies, and the potential for an increase in U.S. onshoring of manufacturing may provide a boost much further down the line.

Against this backdrop, we would not chase the international outperformance seen this year, but we would also not want to be underweight international stocks in a long-term portfolio. A balanced portfolio of high-quality international stocks at reasonable valuations remains an important asset allocation component for long-term investors, in our view.

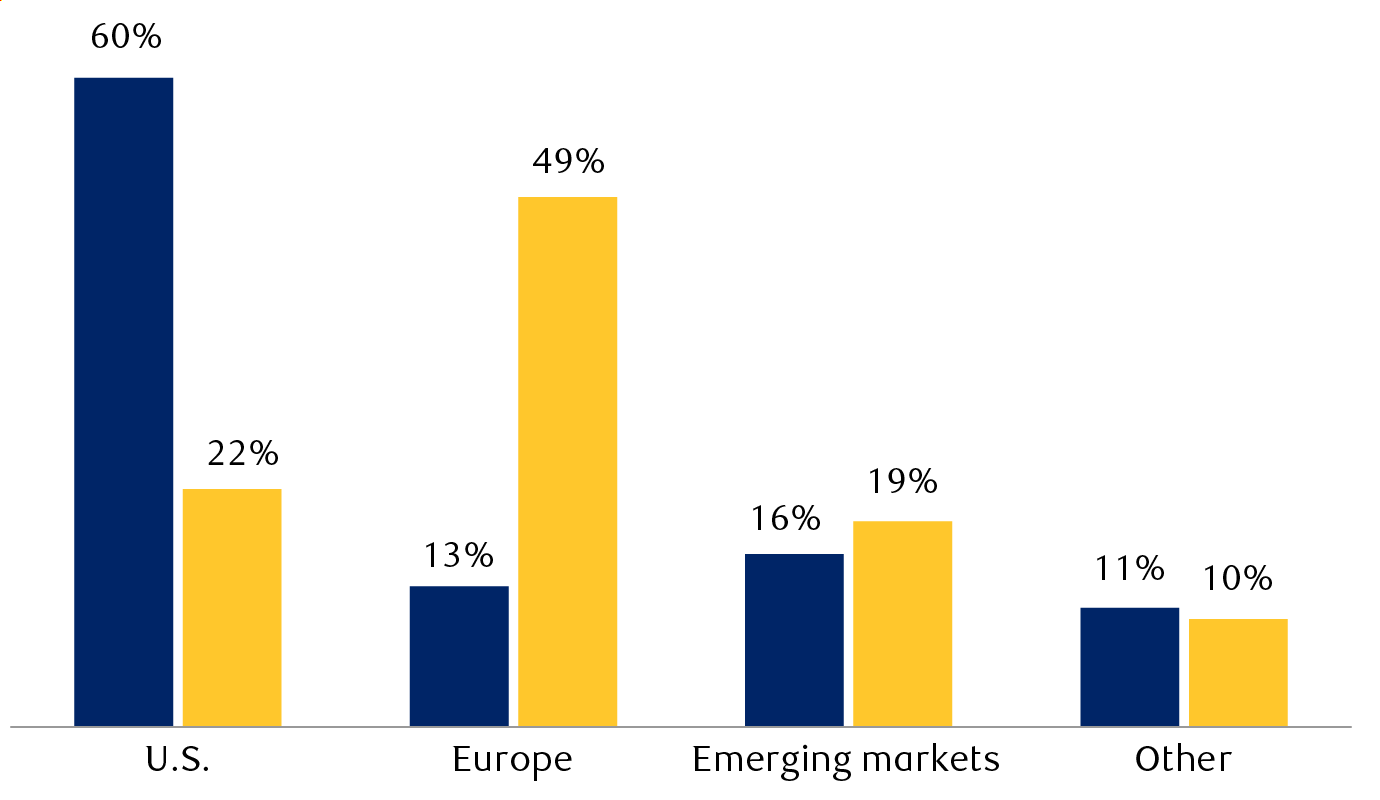

Similar businesses, different customers

U.S. and European stocks’ revenue exposure by region

And if economic growth patterns diverge over the medium term, balanced exposure to end markets in different parts of the world should moderate the risk of an economic misstep in any individual market.

“Wealth management built around you – from one of the world’s strongest firms.”

Let’s Work Together

If you’re seeking guidance, growth, and a partner for the long term, Kate Elizabeth Kurz Wealth Management is here to help. Let’s discuss how our insights can work for you.

Contact Financial Experts To Learn More